Hope Bourne: A Life on Exmoor

- kickasswomen

- Sep 30, 2025

- 5 min read

Have you ever dreamed of going "off-grid"? Of leaving behind the noise, the deadlines, the endless notifications? Of living simply and self-sufficiently, sustained only by what you could grow, gather, or hunt? For most of us, it is just a fantasy, but for Hope Bourne, it was reality. This week's Kickass Women of History explores the extraordinary life of a woman who carved out a solitary, creative existence on the rugged moorlands of Exmoor, and I thought you might like to see some examples of her artwork as context for the episode.

Hope Lillian Bourne was born on 26 August 1918, in Oxford, but spent much of her early life in Devon, with her mother. After her mother died when she was in her early 30s, Bourne left behind conventional domestic life and gradually forged a path in the remoter parts of Exmoor.

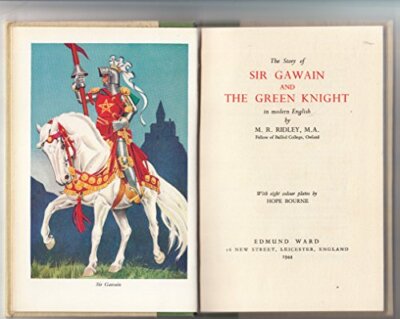

Bourne is perhaps best known for choosing to live in cottages and finally in a caravan on Exmoor, persistently and nearly self‑sufficiently, for much of her life. She grew vegetables, fished, and hunted (especially rabbits) to help feed herself, sometimes trading labour with her with neighbours. Through this time she painted and sketched her environment. She was a self-taught artist, who had once illustrated a children's edition of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. She also kept detailed journals of her life on the moors, which eventually sent to a publisher and launched a prolific writing career.

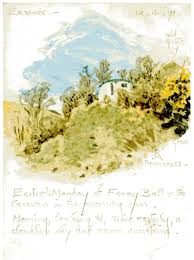

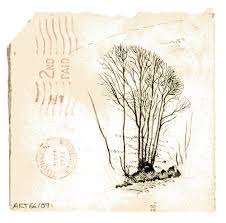

Her lifestyle, though romantic in retrospect, was also austere. She lived without mains power or modern comforts for long periods; she carried water from springs; she re‑used scraps of paper and envelopes for drawings; and she strove to minimize waste.

Bourne’s creativity was multidimensional: she was a painter, sketcher, illustrator, journal keeper, columnist, pamphleteer, and author. She contributed a weekly column to the West Somerset Free Press, and produced books (some published in her lifetime, others posthumously), pamphlets, letters, and more.

A selection of Hope Bourne's art, including illustrations from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, scenes from Exmoor, and images of Bourne painting and at her caravan.

Beyond her vivid descriptions of Exmoor life, Hope Bourne was a passionate advocate for the conservation of the natural environment, often writing with insight and urgency about the need to protect the moor’s delicate ecosystems. Long before terms like "rewilding" became part of mainstream environmental discourse, Bourne was calling for a return to ecological balance, not only through the protection of landscapes, but through the reintroduction of native species long lost from British soil. In her journals and articles, she voiced support for bringing back predators such as lynx, wolves, and even bears, believing that a truly wild Exmoor should reflect the biodiversity it once held. While these ideas may have seemed radical at the time, they now resonate with growing global movements to restore natural habitats and rethink humanity’s role within them. Bourne's vision was clear: to live alongside the wild, not above or apart from it.

Later in life, as health issues (such as asthma) caught up with her, she had to leave the more remote settings and live closer to the village. She died in August 2010, a few days short of her 92nd birthday. Bourne left her estate, along with her manuscripts, drawings, journals, and personal effects, to the Exmoor Society.

“A Life Outside” — the Exhibition

A Life Outside: Hope Bourne on Exmoor opened on 27th September 2025 and runs to 10th January 2026 at the Somerset Rural Life Museum, Glastonbury. It is the first museum exhibition dedicated solely to Bourne’s life and output.

The exhibition is a partnership between the museum, the Exmoor Society (custodian of the Hope L. Bourne Collection), and the South West Heritage Trust. It is co‑curated by Kate Best and Sara Hudston, a writer and Guardian Country Diarist whose forthcoming book, also titled A Life Outside: Hope Bourne on Exmoor, expands on her research. Sara is also the guest expert on this week's episode, giving fantastic insights into Hope Bourne's life and work.

The exhibition draws heavily on the Hope L. Bourne Collection — more than 700 books and pamphlets, over 2,000 sketches and drawings, manuscripts (published and unpublished), photographs, personal items, cuttings, and ephemera.

Visitors will encounter a mix of artworks, personal effects, writings, and archival objects that together conjure Bourne’s world and method:

Sketches and drawings, many rarely seen, capturing moorland views, farm buildings, flora and fauna, often done in pencil, ink or watercolour. Some are drawn on humble materials like envelopes or repurposed paper.

Her journals and published/unpublished manuscripts, giving voice to her reflections, observations and daily rhythms.

Personal effects: items such as her paraffin lamp, Roberts radio, compass, binoculars, Swiss Army knife, and more. These help ground the visitor in the material challenges and modest life she led.

A photograph of her caravan and living quarters (e.g. at Ferny Ball) to give context to her daily environment.

Occasional events and interpretative programming: guided walks, talks, nature writing workshops, and discussion evenings.

The exhibition challenges the view of Bourne as a quaint “hermit artist” and instead presents her as someone whose life choices and ecological sensibilities were purposeful, even prophetic.

Why Hope Bourne Matters Today

Hope Bourne's legacy in conservation and love of the environment speaks powerfully to current cultural and ecological questions.

Resistance in the everyday Bourne’s life suggests that resistance to consumer culture and ecological destructiveness need not be loud or spectacular. Her methods were quiet, incremental, lived. She turned scarcity into aesthetic constraint; necessity into creative fuel.

Landscape as interlocutor, not backdrop Her art and writing never treat Exmoor merely as setting; the moor is interlocutor, subject, companion. Her walks, her mapping, her charting of change over decades remind us that landscapes evolve and we evolve with them.

Loneliness, not romantic solitude Bourne’s solitude was not the romantic solitude of the Romantic poet or the hermit in myth. It carried real physical hardship — illness, isolation, limited social contact. Yet she accepted those costs in order to remain undistracted in her work.

Rediscovery and de‑centering of canonical narratives The fact that Bourne’s work is only now receiving serious museum attention underlines how many voices — particularly rural, marginal, female — are left out of mainstream histories. Exhibitions like this help rewrite that omission.

Ecological foresight In an era of climate urgency and debates about rewilding and land access, Bourne’s voice seems surprisingly forward. She anticipated conversations about land stewardship, low-impact life, rights of access, and rewilding before they were fashionable.

To some, she may still seem an eccentric or local curiosity. But “A Life Outside” invites us to see her more deeply — as a creative thinker whose life was a form of argument, whose solitary lines sketched a different route through the 20th century’s pressures.